Introduction (2): Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind

The second in a series about the journey to this publication and what you can expect from it

It was during the burnout phase of my gigging life that I wandered into a bookstore in uptown Minneapolis and found a copy of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Suzuki Roshi. As soon as I opened it to the first chapter, I was hooked:

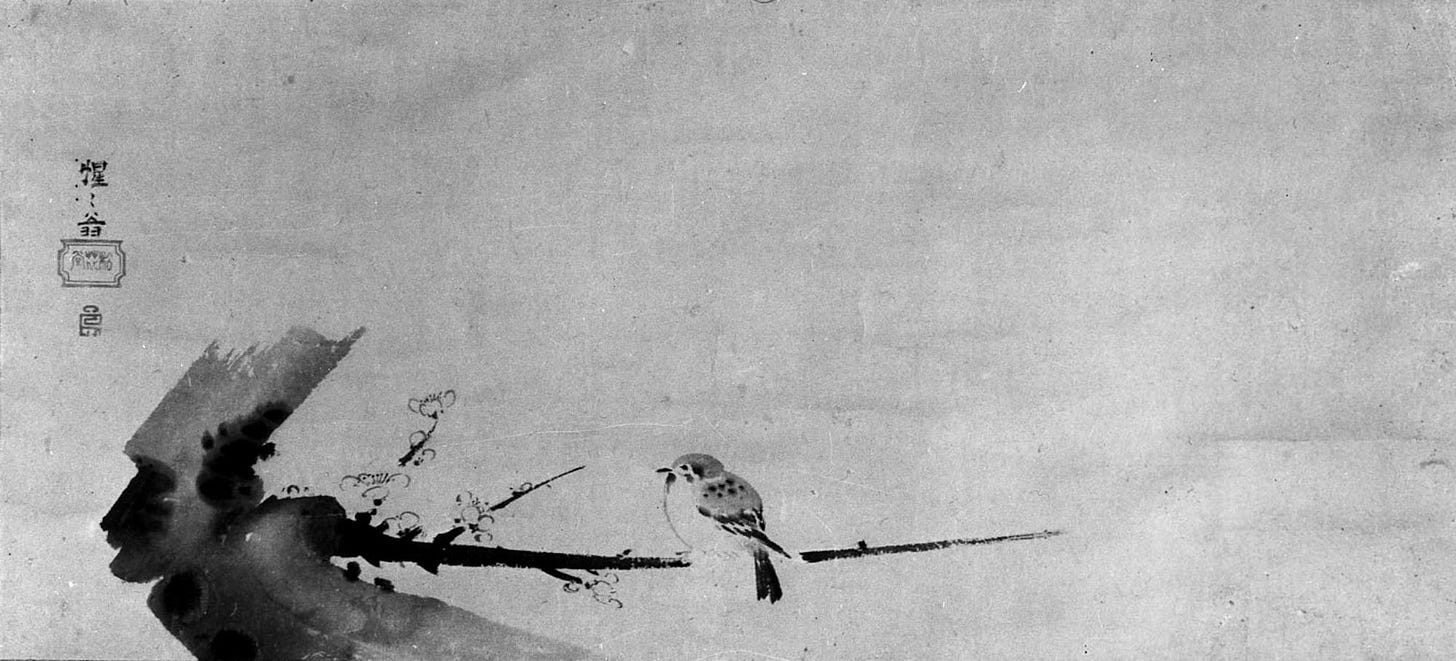

The mind of the beginner is empty, free of the habits of the expert, ready to accept, to doubt, and open to all the possibilities. It is the kind of mind which can see things as they are, which step by step and in a flash can realize the original nature of everything.

What I got from Suzuki Roshi was the idea of metanoia — taking a new path, turning in a new direction, radical reorientation. At any point, even for the expert, it is possible to begin again.

Zen Mind was intoxicating, better than drugs. Behind the words was something noetic and ineffable, a new direction for my guitar playing and my life.

I saw that my whole experience of music had been marked by sharp divides — commercial versus artistic, mediocrity versus virtuosity, disillusionment versus adolescent passion. I sensed the possibilities in shedding my habits, surrendering my beliefs, and rewriting my personal history. Somehow I could get back to beginning, to the primal screaming sound of the guitar gods. I could awaken to the nature of music before it gets hacked up into genres and turned into grist for ego, greed, and self-judgment.

Above all, my aim was to discover how playing impeccably connected to living impeccably. I vowed to learn more about paying attention, breathing consciously, listening deeply, and making music in the service of something bigger than myself.

But how to begin?

For starters, I wanted to stay grounded and not get too spaced out. After all, we’re talking about a material object: A guitar is pieces of wood glued together with tuning pegs and metal frets and six strings attached. The instrument exists in three dimensions. And when we play the guitar, we enter a fourth dimension — time, which can be measured. Everything about the instrument is visible, audible, and empirical.

At the same time, there’s more to consider, things that can’t be measured: What is music? How does it claim us? How does it change us? And why bother with picking up a guitar and playing it in the first place?

Playing well is not just about gaining technique. My guitar gods possessed gobs of technique. They dashed off frenetic riffs that make my jaw drop. They played ballads that made me cry. They knew tons of tunes and played all the “right” notes. And, they had the sound.

But none of that matters much unless you can come into contact with something behind and between the notes — an unspoken quality, a living presence, something that connects with listeners, something that cannot be expressed in words, only in music.

And what is that, exactly? My answers were all clichés: Spirit. Passion. Heart. Soul.

What do all those words mean when you pull your guitar out of its case, strap it over your shoulders, and prepare to play your first note?